Pamela Dellal, mezzo soprano

uncommon intelligence, imagination and textual

awareness... |

|

|---|

- Home

- Resume

- Concerts

- Reviews

- Discography

- Audio Links

- Repertoire

- Teaching

- Photos

- Endicott Players

- Favella Lyrica

- Translations, Essays, and Original Works

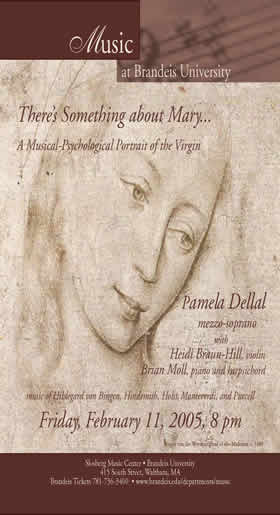

Program notes – There's Something About Mary:

A Musical-Psychological Portrait of the Virgin

performed February 2005

The Virgin Mary has always been the focal point of artists and composers. She represents both the feminine aspect of divinity, and a human every-woman touched by the Eternal. The Catholic Church tended to emphasize her divine qualities, featuring music of praise and supplication to the merciful mother; while Protestant composers, perhaps in reaction to the Catholic Cult of the Virgin, preferred to focus on Mary's human side.

Hildegard von Bingen holds the distinction of being the earliest known woman composer. She was an Abbess and mystic who began having visions in her middle years. She transcribed the content of her visions, including music and poetry as well as vivid images, in a collection of manuscripts. Her fame as a visionary was so great that she was invited to preach in great cathedrals, and was consulted on matters of faith by kings and popes. Today she is most known for her work with herbal healing and her compositions, which are original and extraordinary works. Her 16 antiphons and responsories devoted to the Virgin Mary are distinguished by their focus on the physicality of the Incarnation and Christ's birth, and by their exaltation of femininity through a contrast with Eve’s fall. Filled with virtuosity and expressive dissonance, their idiosyncratic use of mode is thrilling and profoundly moving.

Claudio Monteverdi revolutionized the young art of dramatic monody with his iconic Lamento D'Arianna, an excerpt from the opera Arianna that became so popular that it has outlasted its original context. Within a decade it became one of the most widely imitated pieces of music of the period and influenced the lament for a further 150 years or more. When Monteverdi composed his set of sacred pieces, the Selva morale e spirituale, in the early 1630s, he had the Lamento D'Arianna set to a Latin text focusing on the Virgin Mary at the Cross and titled Pianto della Madonna. The librettist, not credited, chose to remain as faithful as possible to his secular model. The resulting piece, therefore, shows us a Virgin utterly distraught by her Son's death – she displays despair, anger, passion, and all of the volatile emotions that Arianna hurls at Theseus after being abandoned on Naxos. The shock of hearing Mary refer to both her Son and God the Father as sponse (spouse), and rail against his unfeeling abandonment of her, is only slightly mitigated by the allusion to Gethsemane in her ultimate acceptance of her fate. The overt secularism of its source explains such a portrayal at the hands of a Catholic composer.

The Blessed Virgin's Expostulation is undoubtedly one work inspired by Monteverdi's famous lament. Published in Henry Purcell’s collection of sacred solo vocal works Harmonia Sacra, it expands on a small scene in Luke Chapter II, when the twelve-year-old Jesus is inadvertently left behind in Jerusalem by Joseph and Mary. The text presents a doubtful, passionate, and very human Mary who, in her terror at her Son's absence, even wonders whether her vision of the Archangel Gabriel was only a "waking dream." The episodes of dance meter punctuating the highly expressive recitative sections are elements of Italian monody, transformed by Purcell into a unique scena that suggests sacred opera.

Gustav Holst is a British composer best known for his orchestral suite The Planets. While his early works were greatly influenced by Wagner, in later years he became fascinated by Hindu mysticism and the simplicity of English folk song. When he became wildly excited over the rediscovery of English madrigal composers, including Weelkes, Byrd, and Purcell, in the early decades of the 20th century, he was inspired to set English medieval texts. The Four Songs for Voice and Violin, which date from this period, adopt a modal and chant-like style, which harks back to the music of Hildegard. Although the texts of these songs are not directly from Mary's perspective, the melding of love-imagery and the beautiful depiction of the Incarnation in the third song belong to the same emotional landscape as Monteverdi's Pianto and Hildegard's imagery.

In 1923, Paul Hindemith, then a rising star of German Expressionism, published Das Marienleben, a song cycle based on a cycle of 15 poems by Rainer Maria Rilke. In 1948, as a leading exponent of the Gebrauchsmusik movement, he released a revision of these songs. While a few of the songs (#10, 12) remain essentially unchanged, Hindemith explains in an extensive introduction how he rethought and reorganized the song cycle, rejecting a large bulk of his earlier ideas in the process. The earlier songs, he claims, were difficult to sing, the vocal line did not relate to the piano part or sometimes, the poetry, and the songs were not thematically linked to each other to create a unified cycle. In the revised version, his earlier, expressionistic style has largely been replaced with a more conventional melodic line, a consciously restricted harmonic language, and a highly ordered compositional style that includes a variety of formal devices (passacaglia, fugue, theme and variations) and key relationships and motives that carry symbolic meaning and reappear throughout the cycle. The harmonic language is simpler, but at the same time it embraces a broad spectrum: from Renaissance modality to an almost Schönbergian atonality; the studied formalism is not only brilliantly executed, but filled with expressive detail. The two versions of the cycle can be seen in the same light as Schubert's habit of multiple settings of the same poem.

The poem cycle Das Marienleben was a minor work in Rilke's ouvre. His portrayal of the Virgin Mary is drawn from Biblical events and evokes many Medieval images, but is filled with deep psychological insight. One felicity of this cycle is the variety achieved by the change in perspective; Rilke explores third person narrative, the immediacy of the first person voice, and even the highly unusual second person address to the subject (#7 - the Birth of Christ) to paint his portrait. Note how Rilke uses minor references to Mary in the Bible to moving and brilliant effect: Mary's gentle prompt to Jesus at the wedding at Cana, "They have no wine," becomes a defining moment in both their lives -- the point at which his destiny becomes fixed, and hers becomes tragic. Also, the passing reference to the robe woven without seam in John 19:23-24 becomes, in #10 (Before the Passion), a metaphor for Mary's love and tenderness for her son. The two poems on Mary’s death imagine, first, her entrance into heaven and reunion with her Son, and second, the Easter-like discovery of her empty tomb. Due to the length of the work, tonight we are presenting only a portion of the cycle.

© Pamela Dellal