Spohr – Sechs Deutsche Lieder |

Sei still, mein Herz (Karl Friedrich von Schweitzer)

Ich wahrte die Hoffnung tief in der Brust,

Die sich ihr vertrauend erschlossen,

Mir strahlten die Augen voll Lebenslust,

Wenn mich ihre Zauber umflossen,

Wenn ich ihrer schmeichelnden Stimme gelauscht,

Im Wettersturm ist ihr Echo verrauscht,

Sei still mein Herz, und denke nicht dran,

Das ist nun die Wahrheit, das Andre war Wahn.

Die Erde lag vor mir im Frühlingstraum,

Den Licht und Wärme durchglühte,

Und wonnetrunken durchwallt ich den Raum,

Der Brust entsproßte die Blüte,

Der Liebe Lenz war in mir erwacht,

Mich durch rieselt Frost, in der Seele ist Nacht.

Sei still mein Herz, und denke nicht dran,

Das ist nun die Wahrheit, das Andre war Wahn.

Ich baute von Blumen und Sonnenglanz

Eine Brücke mir durch das Leben,

Auf der ich wandelnd im Lorbeerkranz

Mich geweiht dem hochedelsten Streben,

Der Menschen Dank war mein schönster Lohn,

Laut auf lacht die Menge mit frechem Hohn,

Sei still mein Herz, und denke nicht dran,

Das ist nun die Wahrheit, das Andre war Wahn. |

Be Still, my Heart

I harbored hope deep in my breast,

Which embraced it trustingly;

My eyes gleamed full of life’s joy,

As its magic flowed over me;

When I listened to its flattering voice,

In the storm its echo is drowned out.

Be still, my heart, and don’t think on it;

This is now the truth – the other was deception.

The earth lay before me in a dream of spring,

Which light and warmth suffused;

And drunk with delight I explored the surrounds,

Blossoms sprang forth from my breast;

The spring of love was awakened in me –

Frost shivers through me, night inhabits my soul.

Be still, my heart, and don’t think on it;

This is now the truth – the other was deception.

I built, from flowers and sunshine,

A bridge through my life,

Upon which I walked, crowned with laurel,

Dedicated to the noblest of strivings;

The gratitude of humanity was my loveliest reward –

The mob laughs out loud with impudent scorn.

Be still, my heart, and don’t think on it;

This is now the truth – the other was deception. |

Zwiegesang (Robert Reinick)

Im Fliederbusch ein Vöglein saß

In der stillen, schönen Maiennacht,

Darunter ein Mägdlein im hohen Gras

In der stillen, schönen Maiennacht.

Sang Mägdlein, hielt das Vöglein Ruh,

Sang Vöglein, hört das Mägdlein zu,

Und weithin klang der Zwiegesang

Das mondbeglänzte Tal entlang.

Was sang das Vöglein im Gezweig

Durch die stille, schöne Maiennacht?

Was sang doch wohl das Mägdlein gleich

Durch die stille, schöne Maiennacht?

Von Frühlingssonne das Vögelein,

Von Liebeswonne das Mägdelein;

Wie der Gesang zum Herzen drang,

Vergess’ ich nimmer mein Lebelang. |

Duet

In a lilac bush sat a little bird

In the quiet, lovely May night,

Beneath was a girl in the high grass

In the quiet, lovely May night.

The girl sang, the bird kept silence;

The bird sang, the girl listened;

And far and wide their duet rang out

Through the moonlit valley.

What did the bird sing in the branches

Through the quiet, lovely May night?

What was the girl singing at the same time

Through the quiet, lovely May night?

The bird: about spring sun;

The girl: about love’s delight:

And how that song pierced my heart

I will never forget for my entire life. |

Sehnsucht (Emanuel von Geibel)

Ich blick' in mein Herz und ich blick' in die Welt,

Bis von schwimmenden Auge die Träne mir fällt,

Wohl leuchtet die Ferne mit goldenem Licht,

Doch hält mich der Nord, ich erreiche sie nicht.

O die Schranken so eng, und die Welt so weit,

Und so flüchtig die Zeit!

Ich weiß ein Land, wo aus sonnigem Grün,

Um versunkene Tempel die Trauben glühn,

Wo die purpurne Woge das Ufer beschäumt,

Und von kommenden Sängern der Lorbeer träumt.

Fern lockt es und winkt dem verlangenden Sinn,

Und ich kann nicht hin!

O hätt' ich Flügel, durch's Blau der Luft

Wie wollt' ich baden im Sonnenduft!

Doch umsonst! Und Stunde auf Stunde entflieht –Vertraure die Jugend, begrabe das Lied! –

O die Schranken so eng, und die Welt so weit,

Und so flüchtig die Zeit! |

Longing

I look into my heart, and I look at the world,

Until the tears fall from my brimming eyes;

Although the distance shines with a golden light,

The north holds me fast, and I cannot reach it.

Oh, such narrow constraints, and such a broad world,

And time, so fleeting!

I know a country where, out of sunny greenery,

Grapes glow around sunken temples;

Where purple waves foam the banks,

And the laurel dreams of future poets.

From the distance it lures and beckons the yearning mind, and I cannot go there!

Oh, if I had wings; through the blue air

How I wish to bathe in the sun’s fragrance!

But in vain! And hour after hour passes –

Mourning youth, burying song! –

O such narrow constraints, and such a broad world,

And time, so fleeting! |

Wiegenlied (Hoffmann von Fallersleben)

Alles still in süßer Ruh,

Drum mein Kind, so schlaf auch du.

Draußen säuselt nur der Wind,

Su, su, su, schlaf ein mein Kind!

Schließ du deine Äugelein,

Laß sie wie zwei Knospen sein.

Morgen wenn die Sonn' erglüht,

Sind sie wie die Blum' erblüht.

Und die Blümlein schau ich an,

Und die Äuglein küß ich dann,

Und der Mutter Herz vergißt,

Daß es draußen Frühling ist. |

Lullaby

Everything is quiet, in sweetest rest,

My child, so you should also sleep.

Outside the wind only murmurs,

Su, su, su, go to sleep, my child!

Close your little eyes,

Let them be like two buds.

Tomorrow, when the sun shines,

They will blossom like flowers.

And I’ll look at the little flowers,

And I’ll kiss those little eyes,

And the mother’s heart will forget

That it is springtime outside. |

Das heimliche Lied (Ernst Koch)

Es gibt geheime Schmerzen,

Sie klaget nie der Mund,

Getragen tief im Herzen

Sind sie der Welt nicht kund.

Es gibt ein heimlich Sehnen,

Das scheuet stets das Licht,

Es gibt verborgne Tränen,

Der Fremde sieht sie nicht.

Es gibt ein still Versinken

In eine innre Welt,

Wo Friedensauen winken,

Von Sternenglanz erhellt,

Wo auf gefallnen Schranken

Die Seele Himmel baut,

Und jubelnd den Gedanken

Den Lippen anvertraut.

Es gibt ein still Vergehen

In stummen, öden Schmerz,

Und Niemand darf es sehen,

Das schwergepreßte Herz.

Es sagt nicht was ihm fehlet,

Und wenn's im Grame bricht,

Verblutend und zerquälet,

Der Fremde sieht sie nicht.

Es gibt einen sanften Schlummer,

Wo süßer Frieden weilt,

Wo stille Ruh' den Kummer

Der müden Seele heilt.

Doch gibt's ein schöner Hoffen,

Das Welten überfliegt,

Da wo am Herzen offen

Das Herz voll Liebe liegt. |

The Secret Song

There are secret sufferings

That mouths never express,

Carried deep in the heart

They are never made known to the world.

There are secret longings

That always shun the light,

There are hidden tears,

The stranger does not see them.

There is a quiet descent

Into an inner world

Where peaceful meadows beckon,

Illumined by starlight,

Where upon fallen borders

The soul creates its heaven,

And jubilantly confides its thoughts

To its lips.

There is a silent dying

Into mute, desolate pain,

And no one is allowed to see

The heavily burdened heart.

It will not speak of what it lacks,

And even though it breaks with grief,

Bleeding and tortured,

The stranger doesn’t see it.

There is a soft slumber

Where sweet peace dwells,

Where quiet rest heals

The anguish of the weary soul.

Yet there is a more beautiful hope

That soars over all worlds,

where the heart, open to other hearts,

lies full of love. |

Wach auf (Anonymous)

Was stehst du lange und sinnest nach?

Ach schon so lange ist Liebe wach!

Hörst du das Klingen allüberall?

Die Vöglein singen mit süßem Schall;

Aus Starrem sprießet Baumblättlein weich,

Das Leben fließet um Ast und Zweig.

Das Tröpflein schlüpfet aus Waldesschacht,

Das Bächlein hüpfet mit Wallungsmacht;

Der Himmel neiget in's Wellenklar,

Die Bläue zeiget sich wunderbar,

Ein heitres Schwingen zu Form und Klang,

Ein ew'ges Fügen im ew'gen Drang! |

Wake up

Why do you stand so long and ponder?

Ah! love has been awake already so long!

Do you hear the ringing all around?

The birds are singing with a sweet peal;

From the barren spring tender little leaves,

Life flies around bough and branch.

The little drops slide from the forest hollows,

The brook leaps with swelling strength;

The sky bends towards the clear waves,

The blue appears wondrously,

A cheerful whirl of shape and sound,

An endless dance to a constant beat! |

| |

translations © Pamela Dellal |

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel - Six Songs |

Suleika (Marianne von Willemer)

Ach, um deine feuchten Schwingen,

West, wie sehr ich dich beneide:

Denn du kannst ihm Kunde bringen

Was ich in der Trennung leide!

Die Bewegung deiner Flügel

Weckt im Busen stilles Sehnen;

Blumen, Augen, Wald und Hügel

Stehn bei deinem Hauch in Tränen.

Doch dein mildes sanftes Wehen

Kühlt die wunden Augenlider;

Ach, für Leid müßt' ich vergehen,

Hofft' ich nicht zu sehn ihn wieder.

Eile denn zu meinem Lieben,

Spreche sanft zu seinem Herzen;

Doch vermeid' ihn zu betrüben

Und verbirg ihm meine Schmerzen.

Sag ihm, aber sag's bescheiden:

Seine Liebe sei mein Leben,

Freudiges Gefühl von beiden

Wird mir seine Nähe geben. |

Suleika

Ah, over your moist wings,

West wind, how jealous I am!

For you can bring him news

Of my suffering through our separation.

The movements of your wings

Awakens a silent longing in my breast;

Flowers, eyes, forest and hills

Stand tear-bedewed at your breath.

Yet your gentle, soft blowing

Cools the wounded eyelids;

Ah, I would pass away from sorrow,

If I did not hope to see him again.

Hurry then to my beloved,

Speak softly to his heart;

Yet be careful not to trouble him,

And conceal my pain from him.

Tell him, but tell him modestly:

His love is my life.

A joyful feeling of both

Will his presence bring me. |

Verlust (Heinrich Heine)

Und wüßten's die Blumen, die kleinen,

Wie tief verwundet mein Herz,

Sie würden mit mir weinen,

Zu heilen meinen Schmerz.

Und wüßten's die Nachtigallen,

Wie ich so traurig und krank,

Sie ließen fröhlich erschallen

Erquickenden Gesang.

Und wüßten sie mein Wehe,

Die goldnen Sternelein,

Sie kämen aus ihrer Höhe

Und sprächen Trost mir ein.

Die alle können's nicht wissen,

nur Einer kennt meinen Schmerz,

Er hat ja selbst zerissen,

Zerissen mir das Herz. |

Loss

And if the flowers knew, the little ones,

How deeply wounded my heart is,

they would weep with me,

to heal my pain.

And if the nightingales knew it,

how sad and sick I am,

they would joyfully let ring forth

reviving song.

And if they knew my suffering,

the little golden stars,

they would come down from the heights

and speak comfort to me.

All of them could not know it,

only One knows my pain,

indeed He himself has shredded,

shredded my heart. |

Die Mainacht (Ludwig Hölty)

Wenn der silberne Mond

durch die Gesträuche blinkt,

Und sein schlummerndes Licht

über den Rasen streut,

Und die Nachtigall flötet,

wandl' ich traurig von Busch zu Busch.

Selig preis ich dich dann,

flötende Nachtigall,

Weil dein Weibchen mit dir

wohnet in einen Nest,

ihrem singenden Gatten

Tausend trauliche Küsse gibt.

Überhüllet von Laub

Girret ein Taubenparr

Sein Entzükken mir vor,

Aber ich wende mich,

Suche dunklere Schatten,

Und die einsame Träne rinnt. |

The May Night

When the silver moon

flashes through the foliage,

and its sleepy light

streams over the grass,

and the nightingale whistles,

I wander sadly from bush to bush.

I hold you blissful then,

piping nightingale,

since your little wife with you

lives in one nest,

to her singing husband

giving a thousand tender kisses.

Veiled over with leaves

a pair of doves coo

their rapture at me,

but I turn away,

seeking dark shadows,

and my lonely tears fall. |

Dein ist mein Herz (Nikolaus Lenau)

Dein ist mein Herz,

Mein Schmerz dein eigen,

Und alle Freuden die es sprengen;

Dein ist der Wald, mit allen Zweigen,

Den Blüthen allen und Gesängen.

Das Liebste, was ich mag erbeuten

Mit Liedern die mein Herz entführten,

Ist mir ein Wort dass sie dich freuten,

Ein stummer Blick dass sie dich rührten. |

Yours is my Heart

Yours is my heart,

My pain is your own,

And all the joys that make it burst;

Yours is the forest, with all its branches,

All the blossoms and songs.

The best reward I could win

For the songs that seized my heart,

Is one word to me that they pleased you,

Or a silent look, that they touched you. |

Wanderers Nachtlied (Johann W. von Goethe)

Der du von dem Himmel bist,

Alles Leid und Schmerzen stillest,

Den, der doppelt Elend ist,

Doppelt mit Erquikkung füllest.

Ach! Ich bin des Treibens müde,

Was soll all der Schmerz und Lust?

Süßer Friede, süßer Friede!

Komm, ach komm in meine Brust! |

Wanderer's Night Song

You who are from heaven,

who quiets all sorrow and pain,

him, who is doubly wretched,

you fill doubly with refreshment.

Alas! I am weary of striving,

what is all the pain and joy for?

Sweet peace, sweet peace!

Come, ah, come into my breast! |

Zauberkreis (Friedrich Rückert)

Was steht denn auf den hundert Blättern

Der Rose all?

Was sagt denn tausendfaches Schmettern

Der Nachtigall?

Auf allen Blättern steht, was stehet

Auf einem Blatt,

Aus jedem Lied weht, was gewehet

Im ersten hat.

Daß Schönheit in sich selbst beschrieben

Hat einen Kreis,

Und keinen andern auch das Lieben

Zu finden weiß.

Drum kreist um sich mit hundert Blättern

Die Rose all,

Und um sie tausendfaches Schmettern

Der Nachtigall. |

Magic Ring

What stands upon all hundred petals

Of the rose?

What does the thousand-fold warbling

Of the nightingale say?

On all the petals lie what is

On each:

Out of every song wafts what the first one

Breathed:

That beauty has inscribed itself

In a circle,

And even Love does not know

How to find another.

Therefore the rose encircles itself with

A hundred petals,

And the nightingale surrounds itself with

Thousand-fold songs. |

| |

translations © Pamela Dellal |

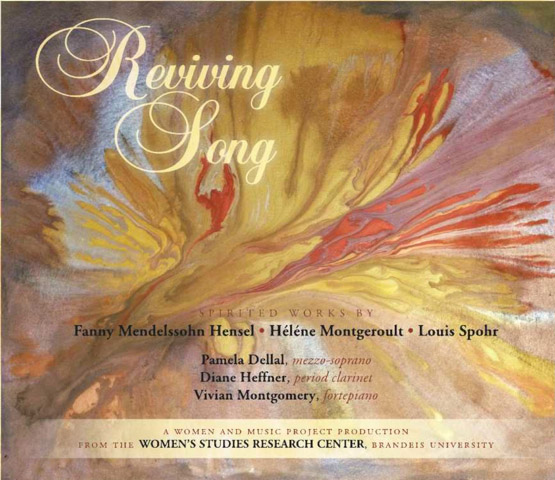

Reviving Song:

Spirited Works by Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, Héléne Montgeroult & Louis Spohr

Pamela Dellal, mezzo-soprano

Diane Heffner, period clarinet

Vivian Montgomery, fortepiano

A Women and Music Project Production

from the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University

Sechs deutsche Lieder für eine Singstimme, Klarinette, und Klavier, op. 103

(Six German Songs for Voice, Clarinet, and Piano)

Louis (Ludwig) Spohr (1784-1859)

Sonata III in F minor, Opus 1

Heléne Nervo de Montgeroult (1764-1836)

Lieder

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (1805-1847)

Recorded at Brandeis University’s Slosberg Recital Hall, January 2010.

Performed on the Brandeis Joseph Worel fortepiano, Vienna (1835), restored by Keith Hill

and a copy of a clarinet by H.Grenser, Dresden (1810), made by Daniel Bangham.

Engineered and edited by Frank Cunningham.

Fortepiano tuning and maintenance by Tim Hamilton.

Funded by the WSRC Women and Music Project.

Special thanks to Dr. Liane Curtis, Dr. Shula Reinharz, and the Brandeis University Department of Music, with particular gratitude for the spirit of Mary Ruth Ray.

Cover art by Lil McGill.

In memory of Ruth Shimony Montgomery. |

Artist Biographies

Pamela Dellal, mezzo-soprano, has enjoyed a distinguished career as an acclaimed soloist and recitalist. She has appeared in Symphony Hall, the Kennedy Center, Avery Fisher Hall, and the Royal Albert Hall, and premiered a Harbison chamber work in New York, San Francisco, Boston and London. Ms. Dellal has received critical acclaim for performances of Brahms' Alto Rhapsody, Handel's Messiah, Mozart's C-minor Mass, and Bach's B-minor Mass, St. Matthew and St. John Passions. Operatic appearances include leading roles in the operas Alcina, Albert Herring, Dido and Aeneas, La Clemenza di Tito, Così Fan Tutte, Vanessa, The Rape of Lucretia, and Winter’s Tale. She has been featured by the Handel and Haydn Society, Aston Magna, The Boston Early Music Festival, Tokyo Oratorio Society, Opera Company of Boston, the National Chamber Orchestra, Boston Baroque, Baltimore Choral Arts Society, and the Dallas Bach Society, appearing in concert in major cities in Europe, the United States, Australia and Japan.

Known for her work with Renaissance and Baroque chamber music, Ms. Dellal has appeared multiple times with the Boston Early Music Festival, Ensemble Chaconne and the Musicians of the Old Post Road, and is a current member of the Blue Heron Renaissance Choir. With Sequentia Ms. Dellal has made numerous recordings of the music of Hildegard von Bingen. A passionate advocate for contemporary music, she has been a regular guest with the Boston ensembles Dinosaur Annex and Boston Musica Viva, premiering works by Boykan, Brody, Lomon, Wheeler, and others. She has been a regular soloist in the renowned Bach Cantata series presented by Emmanuel Music since 1984, having performed almost all 200 of Bach's sacred cantatas. She has over twenty-five recordings to her credit, on the Artona, BMG, CRI, Dorian, Meridian, and KOCH labels among others.

As a period clarinet specialist, Diane Heffner performs regularly with Boston Baroque, Handel & Haydn Society, Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra (San Francisco), Arcadia Players, and has appeared with Opera Lafayette (DC), The American Classical Orchestra (New York), Rebel Baroque Orchestra (New York), Musicians of the Old Post Road, Chicago Opera Theatre, the Classical Arts Orchestra (Chicago), the Dayton Bach Society, Portland Baroque Orchestra (Oregon), the Connecticut Early Music Festival, the Boston Early Music Festival, and the American Bach Soloists (California). Diane has been touring occasionally with Musica Angelia on their projects with actor John Malkovich, "The Infernal Comedy" and "The Giacomo Variations." She has recorded with many of these ensembles on the Philharmonia Baroque, Telarc, Erato, Harmonia Mundi, Cedille, CRI, Arabesque, GM, Koch, and Troy record labels.

On modern clarinet, she is a member of Dinosaur Annex Music Ensemble, Alea III, Alcyon Chamber Ensemble, Solar Winds, and appears with the Vermont Symphony Orchestra, the Boston Gay Men's Chorus, and other assorted freelance ensembles. Branching out into the jazz world on saxophone and clarinet, Diane is part of a 4-piece jazz/blues/r&b combo, "Kate and the Finn-Tones," and Boston's only 20 piece all women big band, "The Mood Swings Orchestra. She is on the applied faculty at Tufts University, the Cambridge School of Weston, and the All-Newton Music School. Diane received both BM and MM degrees with honors from the New England Conservatory where she studied clarinet with Joseph Allard and chamber music with Rudolph Kolisch and Leonard Shure.

Vivian Montgomery, fortepianist, is a prize-winning early keyboardist, praised for her "…exquisite music-making...exceptional for its precision, blend and stylistic unity...sprightly and charming" (Music in Cincinnati). Recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship as well as an Individual Artist Award from the National Endowment for the Arts, Vivian served on the faculty of the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music from 2003 to 2013, teaching early keyboards and historical performance. Having earned her Masters in Early Keyboards from the University of Michigan and the DMA in Early Music from Case Western Reserve University, Vivian has served as Director of the Jurow International Harpsichord Competition since 2009. Her performing life encompasses concerto solos, solo recitals, chamber music performances, and vocal accompanying work throughout the United States. She has recently been heard in numerous performances of 19th-century American and women’s music, and her work on little-known piano music for domestic use is captured by the upcoming Centaur Records release entitled Brilliant Variations on Sentimental Songs. While building on collaborations as half of the period instruments duo Adastra and the dynamic Galhano/Montgomery Duo, Vivian has also explored, throughout her career, the musical lives of women from 1500 to 1900, especially through two decades of cross-disciplinary work with her ensemble, Cecilia’s Circle. Recordings can be found on the Centaur, Schubert Club and Innova labels. Her work as a conductor has led to engagements directing baroque opera, orchestras, and choirs in Minneapolis, Cleveland, Pennsylvania, and in her current residence, Boston. Vivian holds a post as a Resident Scholar at the Brandeis University Women’s Studies Research Center, where she is founder and chair of the Women and Music Mix. |

| Liner Notes

Reviving Song is the product of numerous intersections and coincidences. In the fall of 2008, I became part of the glorious synergy that is the Women’s Studies Research Center at Brandeis University. As, at the time, a Visiting Scholar, I was committed to work on a variety of projects revolving around the lives and work of women composers, with a special emphasis on their place at the piano, specifically in intimate and domestic settings, more specifically in the early nineteenth century. A post-doctoral publication grant from the American Association of University Women was intended to support my work on the young woman pianist’s self-expression through variation treatments of “favorite” tunes in Antebellum America, but it also helped to carved out a complex of other projects in collaboration with my WSRC colleague Liane Curtis, among others. Several of the projects were stimulated by the relatively recent arrival in the Brandeis Department of Music of a newly restored Viennese fortepiano. Liane and I had both long been admirers of the works of Héléne Montgeroult, with her unique rhythmic play and swirling gestures, and this instrument surpassed all others I had access to in its appropriateness for performing her piano music. It was similarly suited for accompanying mid-nineteenth-century German and Viennese vocal music, and the songs of Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel had been a preoccupation of mine for some time: their poetry and harmonic vocabulary beckoned but for many years the right instrument, for capturing the real sonic environment of Fanny’s music, had been elusive. For Pamela Dellal, who taught voice at Brandeis and who had already performed many of Fanny’s songs, the presence of the fortepiano there had suggested new forays into this composer’s output, and she was enthusiastic when I suggested we put together a program that included a substantial set. Simultaneously, I had started conversations with Diane Heffner about the rarity of opportunities available in Boston for playing romantic chamber music, such as the clarinet songs of Louis Spohr, on period instruments. The absence of an ideal fortepiano for this repertoire played a part in this deficit – Schubert and the Mendelssohns hardly made sense on a Mozart-era fortepiano – so the Brandeis instrument brought some much-needed momentum to that pursuit.

So there was a concert program and, about 8 months later, in the cold and quiet first days of 2010, a recording. In the intervening months, my mother had declined and then passed away; after decades of being my most ardent advocate and having shown infinite tolerance for my halting progress at the keyboard, the last live performance she was able to attend of mine was at Brandeis, on this instrument. Also present at the live performance of these works were two other enthusiastic spirits since passed from our realm: my oldest friend Persephone Miel and Brandeis music department chair Mary Ruth Ray, whose warm support of anything involving the Brandeis fortepiano made it easy to persist in the face of numerous logistical and technical obstacles. In remembering such beneficent souls, we “… joyfully let ring forth reviving song.”

Yet there is a more beautiful hope

That soars over all worlds,

where the heart, open to other hearts,

lies full of love.

© Vivian Montgomery

Notes on Composers

Louis Spohr (b Brunswick, 5 April 1784; d Kassel, 22 Oct. 1859) was a German composer and violinist who launched his career in the Brunswick court establishment in 1799. During 1802–3 he studied with Franz Eck on a journey to St Petersburg, and in 1805, after a highly successful concert tour in Germany, performing his own concertos, he gained the post of Konzertmeister in Gotha, where he married the virtuoso harpist Dorothea Scheidler. His reputation as violinist and composer was increased by many concert tours with his wife, during which he played his own violin concertos as well as duets for violin and harp. In 1812 Spohr moved to Vienna as Konzertmeister at the Theater an der Wien, composing operas as well as his acclaimed Eighth Violin Concerto, in the form of an extended vocal scena, In 1816–17 for a concert tour to Italy, where his cantabile style of playing was greatly relished. On his return he became Kapellmeister at the Frankfurt theatre, and from 1822 Spohr was Kapellmeister in Kassel. In 1830–1 he wrote his Violinschule, which remained a classic violin method into the 20th century, and between 1839 and 1853 he made five triumphant visits to England, where his oratorios were highly esteemed and where his instrumental music and operatic numbers were regularly given in orchestral concerts. He created his own, highly individual version of the bravura “Viotti style” and played a significant part in the development of conducting. His influence as a composer was much greater than posterity has generally recognized. During the 1810s and 20s many young composers were fascinated especially by his handling of chromatic harmony, and his style was widely imitated, leaving traces in the music of numerous important and less well-known composers. However, his music failed to evolve stylistically after the early 1830s and he was often charged with mannerism by less sympathetic critics. His posthumous reputation suffered from the artistic politics of the later 19th century. Nevertheless his finest works are among the most significant of their time and remain capable of giving pleasure and evoking admiration.

- extracted from biographical notes of Clive Brown

Hélene-Antoinette-Marie de Nervo de Montgeroult (b Lyons, 2 March 1764; d Florence, 20 May 1836) was a French virtuoso fortepianist and composer, trained in Paris by N.-J. Hüllmandel, Clementi (1784) and then J.L. Dussek and later studying with Antoine Reicha. In 1784 she married the Marquis de Montgeroult (d 1793), then Charles-Hyacinte His, whom she divorced in 1802, and finally the Count du Charnage (d 1826). In 1795 she was appointed professeur de première classe at the newly established Paris Conservatoire, where she taught numerous illustrious musicians. Her home was later recognized as one of the most important Parisian musical salons, where she performed her own works and collaborated with other like-minded musicians. She was particularly integral to the intimate circles that contained violinist Giovanni Battista Viotti and Montgeroult’s teacher Hüllmandel, and there are questions about whether some of those composer’s works might contain borrowings from Montgeroult, if not being outright misattributed. At the turn of the century she published her two collections of Trois sonates pour le forte-piano and later a Cours complet pour l’enseignement du forte-piano (in three volumes, around1820), which was praised as an important resource of musicianship. She was widely recognized for her passionate improvisational practice, and a further treatise by Montgeroult applied the art of singing to playing the piano. She died while travelling in Italy and is buried in the cloister of San Croce in Florence.

- indebted to Oxford Music entry by Julie Anne Sadie

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (b Hamburg, 14 Nov 1805; d Berlin, 14 May 1847) was a German composer, pianist and conductor, often heard of first as sister of the composer Felix Mendelssohn. She was the eldest of four children born into a post-Enlightenment, cultured Jewish family. Of her illustrious ancestors, her great-aunts Fanny Arnstein and Sara Levy provided important role models, especially in their participation in salon life. Her paternal grandfather, Moses Mendelssohn, was the pivotal figure in effecting a rapprochement between Judaism and German secular culture. In Fanny Mendelssohn’s generation this movement resulted in the conversion of the immediate family to Lutheranism. Despite baptism, however, Fanny retained the cultural values of liberal Judaism. An important element in the family circle was her special relationship with her younger brother Felix (1809–47). In close contact their entire life, they stimulated and challenged each other musically and intellectually. Fanny played a major role in shaping some of Felix’s compositions, notably his oratorio St Paul (completed in 1837), and advised him on musical matters. Felix, likewise, encouraged her compositional activities, but he discouraged publication. Although his attitudes echoed his father’s views and reflected the prevailing cultural values, they may have been motivated by jealousy, fear of competition, protectiveness or paternalism. In any case, these negative aspects exacerbated Fanny’s own feelings of ambivalence towards composition. She depended on Felix’s good opinion of her musical talents, as expressed in a letter to him of 30 July 1836, where she speaks of a Goethe-like demonic influence he exerted over her, and said that she could ‘cease being a musician tomorrow if you thought I wasn’t good at that any longer’. But after Felix’s marriage in 1837, their relationship became less intense. In 1846 Fanny embarked on publication without her brother’s involvement: her pointed avowal of independence suggests pent-up frustration on this sensitive issue. From 1809 Fanny Mendelssohn lived in Berlin and her first composition dates from December 1819, a lied in honour of her father’s birthday. In 1820 she enrolled at the newly opened Berlin Sing-Akademie, and during the next few years produced many lieder and piano pieces; such works were to be the mainstay of her output of about 500 compositions. On 3 October 1829 she married the Prussian court painter Wilhelm Hensel. Beginning in the early 1830s, Mendelssohn became the central figure in a flourishing salon, for which she created most of her compositions and where she performed on the piano and conducted. Her tastes favoured composers who were then unfashionable, including Mozart and Handel, and especially Bach. Her only known public appearance was in February 1838, performing her brother’s First Piano Concerto at a charity benefit. Her last composition, the lied Bergeslust, was written on 13 May 1847, a day before her sudden death from a stroke. Many modern editions of Fanny have now appeared, but the great majority of works are still in manuscript. Fanny Mendelssohn’s letters and diaries reveal a witty, perceptive and intelligent woman, fully conversant with intellectual life. Her strong self-image in this regard contrasts with her shaky confidence in her creativity (not uncommon in women composers). Yet despite her doubts, she created and maintained in her salon a flourishing showcase for her many musical talents. Any full-scale evaluation will have to take into account the importance of the salon for Mendelssohn as for countless other female composers, writers and artists.

- extracted from Marcia Citron’s entry in Grove Online |

|